Are sharks the boss of the Great Barrier Reef?

On the Great Barrier Reef sharks are readily identified as fearsome predators. In ecological theory, species that are at the top of the food chain are commonly described as apex predators. However generalising all sharks as apex predators is misleading and may lead to poor outcomes in the context of managing coral reefs and sharks for conservation.

Dr Michelle Heupel has set up acoustic monitoring stations which record the presence and movement of sharks between the coast and the reef, and between reefs. Up to July 2014 she has tagged 220 sharks of nine species to monitor their movement behaviour around corals reefs. She said "as we get more sharks tagged and more data from acoustic array it is becoming apparent that different types of sharks and different life stages make very different use of reefs as predators."

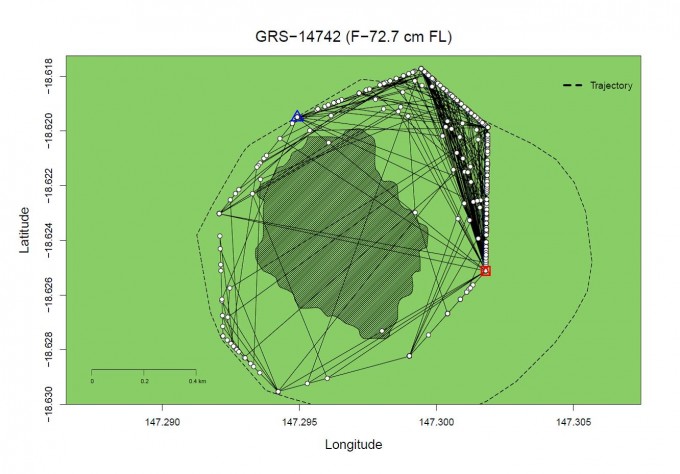

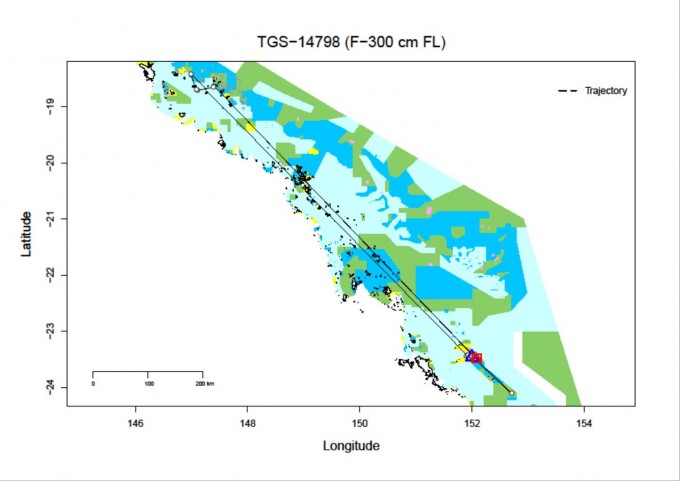

An example that demonstrates how movement patterns can inform better definitions of the functional roles of sharks on the Great Barrier Reef is to compare the track of a grey reef shark and tiger shark, both of which were recorded in Dr Heupel's acoustic arrays over a period of several months after being tagged. The grey reef shark roamed around a single reef near Townsville. The tiger shark travelled from Heron Island north to Townsville, down to Lady Elliot Island and back to Heron Island, a journey of over 3000 km in just over 12 months.

Dr Heupel said the role of predators such as sharks within marine ecoystems needs to be better described and defined. Mature individuals of large bodied sharks such as tiger sharks are best described as apex predators, but smaller sharks and young animals of larger species are best described as mesopredators1. Mesopredators are any mid-ranking predator in a food web, regardless of size or species. The difference, Dr Heupel said, is important for both the protection of sharks, and in determining how shark diversity and abundance affects coral reef resilience.

For example, studies have shown there is a high overlap in diet between similar-sized sharks regardless of age and species identity2. If we consider small bodied sharks as a community of mesopredators, ecological theory would predict changes in one species would have little impact on the overall dynamics of the ecosystem. Large sharks eat larger prey, have higher energetic requirements and larger feeding areas. If large sharks are selectively removed through culling or fishing, theory predicts an increase in small size class predators, potentially leading to increased predation pressure on reef dwelling fish3.

Dr Heupel said while mobility of sharks in and out of marine park zones is one issue, sharks roles as predators has other ecological implications for coral reefs that can be better managed by considering life history traits rather than species-based classifications.

Sharks are the boss of the reef, but large mobile apex predators such as tigers, hammerheads and bull sharks are the most vulnerable in conservation frameworks based only on Marine Protected Areas. Their removal or decline is predicted to have more flow-on effects to reef communities than for smaller sharks. Therefore conservation management needs to consider the needs of both small and large species to be effective.

1. Heupel, M., Knip, D., Simpfendorfer, C. & Dulvy, N. Sizing up the ecological role of sharks as predators. Marine Ecology Progress Series (2013). doi:10.3354/meps10597

2. Bethea, D. M., Buckel, J. A. & Carlson, J. K. Foraging ecology of the early life stages of four sympatric shark species. Marine Ecology Progress Series 268, 245-264 (2004).

3. Steneck, R. & Sala, E. Large marine carnivores: trophic cascades and top-down controls in coastal ecosystems past and present. (2005).