Articles

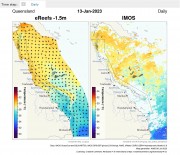

This section shows the latest temperature and ocean current estimates from remote sensing (Ocean current IMOS) and two different hydrodynamic models: CSIRO eReefs model and the BOM eReefs model. Each of these products have their own websites where more detailed views can be found.

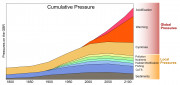

Over the last fifteen years a number of major efforts have significantly expanded the sustained monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR).

Understanding the management and governance of Australia’s vast coastline can be complex. International, Commonwealth, State and Indigenous entities all have various roles and powers to promote the health and integrity of Australia’s marine environments.

Sponge taxonomy is difficult and challenging, it requires adequate laboratory facilities, experience and time, which are often not available. Moreover, not all habitats can be physically sampled (e.g. protected areas, deep sea), and for monitoring purposes video work is usually the preferred method. However, sponges cannot reliably be identified from imagery lacking samples, and therefore we recommend using growth forms as a quick classification. If the growth forms are described by clearly focusing on their function, they will represent environmental conditions, e.g.

Tiger sharks have a worldwide distribution and although tending to be concentrated in tropical waters are also commonly found in temperate waters (Pepperell, 2010). They are found in all the project jurisdictions and, although they tend to frequent continental shelf waters are also known to take large-scale oceanic migrations (Holmes et al. 2014; Werry et al. 2014). Along the Australian east coast large-scale movements of tiger sharks through Torres Strait, the GBR and Great Sandy Strait are common (Werry et al. 2014).