Pisonia connectivity

Pisonia; or Birdlime Tree (due to the fact that at times nesting birds become covered with the sticky fruits).

On coral cays, pisonia forests are tolerant of temporary saltwater and freshwater inundations and can tolerate full water lenses and waterlogged conditions better than other woody competitors. Pisonia are, however, prone to shed branches during storms; the fallen trees and/or branches sprout and revegetate the damaged forest areas. Pisonia wood is rather weak and soft and decays rapidly after the trees fall.

In Australia there is only approximately 190 Ha of Pisonia forests, and around 80% of Australia’s Pisonia forests grow on the Capricorn Cays within the Great Barrier Reef.

Distribution: Pisonia trees are distributed in Northern Territory, Cape York, north Queensland and southwards as far as coastal central Queensland and throughout the coral cays of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, SE Asia, and Malesia.

Distribution map: see https://bie.ala.org.au/species/http:/id.biodiversity.org.au/node/apni/2899632

Introduction to the Pisonia connectivity and why it is important

Pisonia forests are common nesting sites often inhabited by large numbers of seabirds, particularly noddies, which roost in the trees each night. Faeces, food scraps, dead chicks and expired adults are a major source of nutrients and Pisonia trees thrive on these nutrients (Turner and Batinoff, 2007).

"Several island bird species will be at risk if their Pisonia closed-forest habitat disappears through rising sea level inundation and erosion. On the Capricorn Bunker Cays, the Capricorn white-eye will lose its major habitat, black noddies (Anous minutus) will no longer have Pisonia branches to nest on and wedge-tailed shearwaters (Puffinus pacificus) will no longer have Pisonia root mass to support their burrows and bare ground to walk on under pisonia trees. On Tryon Island (Capricorn Bunker Group) where Pisonia closed-forest was lost through insect attack, shearwater nesting has substantially declined (P O’Neill pers comm)" (Turner and Batinoff, 2007).

There are many islands with shrub and grass vegetation in the GBR but few with Pisonia closed-forest, and black noddies and wedge-tailed shearwaters may have few other options for nesting sites (Turner and Batinoff, 2007). Where Pisonia forest has been lost, Black noddies may nest on other trees, such as casuarinas on Lady Elliott Island (B Knuckey, pers comm), but their nesting success may be reduced (Turner and Batinoff, 2007).

"Pisonia closed-forests have special physiological and morphological adaptations to withstand environmental stresses such as drought and seawater inundation and may replace rainforest species. However, if inundation of freshwater lenses continues, Pisonia forest will eventually be replaced by more tolerant arboreal shrubs such as Abutilon albescens and Heliotropium foertherianum, and ground cover plants... These shrubs and grasses will take over as Pisonia trees die, creating glades and open sunlit areas. These scenarios have already been observed on Tryon Island, Capricorn Bunker Group" (Turner and Batinoff, 2007).

Key concepts that relate to connectivity

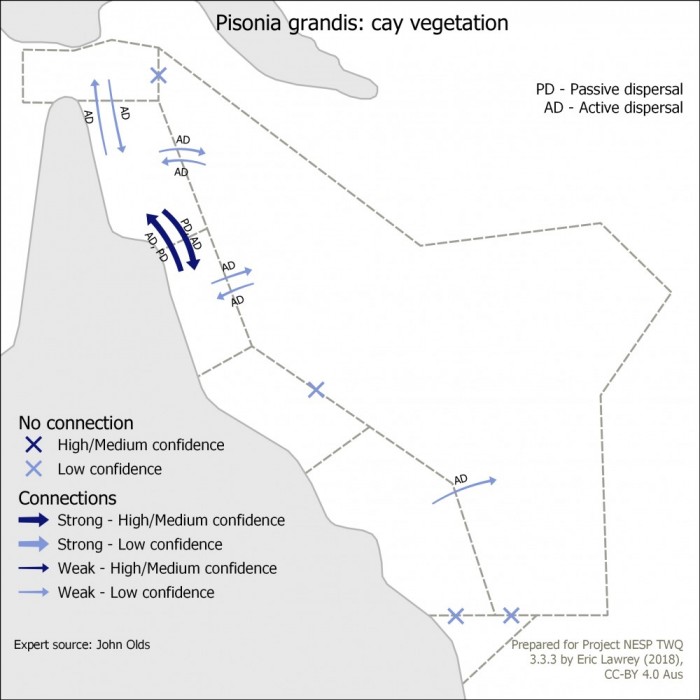

Unlike many other coastal plants which have fruits or seeds that float and which are readily dispersed by the ocean, the fruits of P. grandis are clearly adapted for dispersal by birds (Walker, 1991). "The fruits are small and sticky and remain attached to the branched fruiting heads which, when lying en masse on the sand below the trees, are unavoidably brushed by nesting sea birds. The whole fruiting head is thus carried by the bird, glued to the feathers on the body or wings, to other islands" (Brock, 1988)

Under climate change, the existing beach scrub trees will be displaced and will be replaced by salt tolerant woody plants including coastal she-oak (Casuarina equisetifolia); consequently such tolerant plants are likely to expand their range along the coast and on some GBR islands.

Considerable damage on the Pisonia forests of Tryon and Wilson Islands in the Capricorn Bunker Group was caused by scale insects (Pulvinaria urbicola) (Kay 2003). The scale can be regarded as an exotic pest to Australia and is normally biologically controlled by two small wasp parasitoids Coccophagus ceroplastae and Euryischomyia flavithorax or the ladybird Cryptolaemus montrouzieri. These natural enemies effectively control the scale in eastern Australia and the two parasitoids have been very effective on islands of the Capricorn Group. The scale attacking fungus Verticillium lecanii is another biocontrol option.

In the Coral Sea, a March 2001 report showed the levels of P. urbicola on Pisonia forests on North East Herald Islet increased 150 fold since a previous assessment in December 1997 (Smith and Papacek, 2001). The infestation spread through the islet with many hot spots with scale numbers over 100 per leaf. No parasitoids were recorded and there was little if any predation. Similar scale levels were recorded on Coringa Islet in December 1997 and there was only one small heavily infested tree left. Revegetation of Coal Sea Islets with P. grandis trees will therefore depend on successful bio-control of P. urbicola.

Dispersal of P. urbicola to the Coral Sea Islets seems likely to have been by seabirds; human involvement appears less likely (Smith and Papacek, 2001). However, visitors to the Coral Sea Islets should be aware of a quarantine protocol which should prelude introduction of soil, firewood or vegetative material. All fresh fruit and vegetable scraps should be carried off the islets. Equipment should be clean and free of dirt, insects, spiders or small animals.

Invasive ant species which threaten native ants and other arthropods with their aggressive behaviour and ability to colonize large geographic areas, pose another serious threats to island ecosystems.

References

Brock, John (1988). Top End Native Plants. Self-published. ISBN 0 7316 0859 3

Kay A (2003). The impact and distribution of the soft scale Pulvinaria urbicola in the Pisonia grandis forests of the Capricorn Cays National Parks. Report, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service.

Smith, D and D. Papacek, D (2001) Report on the Levels of the Scale Insect Pulvinaria Urbicola and its Natural Enemies on Pisonia Grandis in the Coringa-Herald National Nature Reserve 16-23 March 2001 Report for Environment Australia. https://www.environment.gov.au/resource/report-levels-scale-insect-pulvinaria-urbicola-and-its-natural-enemies-pisonia-grandis

Turner, M and Batianoff, GN (2007). Chapter 20, Vulnerability of island flora and fauna in the Great Barrier Reef to climate change. In Climate Change and the Great Barrier Reef, eds. Johnson JE and Marshall PA. GBRMPA and Australian Greenhouse Office, Australia.

Walker TA (1991) Pisonia islands of the Great Barrier Reef. Part I. The distribution, abundance and dispersal by seabirds of Pisonia grandis. Atoll Research Bulletin 350, 1-23.