Declining Coral Calcification on the Great Barrier Reef

Reef-building corals are under increasing physiological stress from a changing climate and ocean absorption of increasing atmospheric CO2. We investigated 328 colonies of massive Porites corals from 69 reefs of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Their skeletal records show that throughout the GBR, calcification has declined by 14.2% since 1990, predominantly due to extension declining by 13.3%. The data suggest such a severe and sudden decline in calcification is unprecedented in at least the last 400 years. Calcification increases linearly with increasing large-scale sea surface temperature, but responds non-linearly to annual temperature anomalies. The causes for the decline remain unknown, however this study suggests that increasing temperature stress and declining seawater aragonite saturation state may be diminishing the ability of GBR corals to deposit calcium carbonate.

There is little doubt that coral reefs are under unprecedented pressure worldwide due to climate change, changes in water quality from terrestrial runoff, and overexploitation (1). Recently, declining pH of the upper seawater layers due to the absorption of increasing atmospheric CO2 (termed ocean acidification; (2)) has been added to the list of potential threats to coral reefs, as laboratory studies show coral calcification decreases with declining pH (3, 4, 5, 6). Coral calcification is an important determinant of the health of reef ecosystems, as tens of thousands of species associated with reefs depend on the structural complexity provided by the calcareous coral skeletons. Several studies have documented globally declining coral cover (7) and reduced coral diversity (8). However, few field studies have so far investigated long-term changes in the physiology of living corals as indicated by coral calcification.

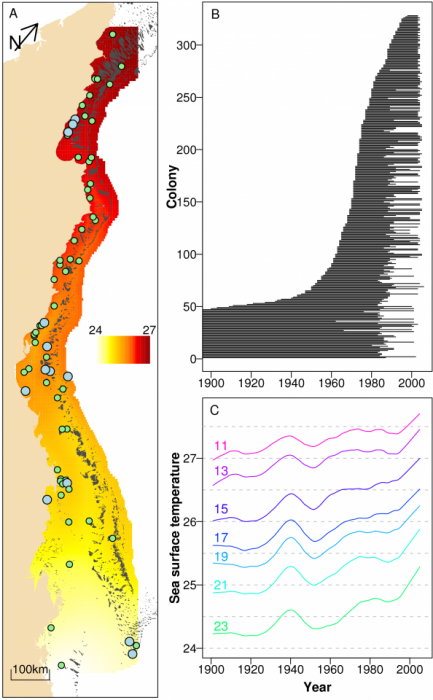

We investigated annual calcification rates derived from 328 colonies of massive Porites (Coral Core Archive of the Australian Institute of Marine Science; (9, 10)) from 69 reefs ranging from coastal to oceanic locations and covering most of the >2000 km length of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR, Latitude 11.5 – 23º South; Figs. 1A and B). Like other corals, Porites grow by precipitating aragonite onto an organic matrix within the narrow space between their tissue and the previously deposited skeletal surface. Massive Porites are commonly used for sclerochronological studies as they contain annual density bands (11), are widely distributed, and can grow several centuries old. Numerous studies have established that changes in environmental conditions are recorded in their skeletons (12).

Annual data for the three growth parameters, skeletal density (g cm-3), annual extension (cm yr-1) and calcification rate (the product of skeletal density and annual extension; g cm-2 yr-1) were obtained from each colony using standard x-ray and gamma densitometry techniques (10, 13). Mean annual sea surface temperature (SST) records were obtained from the HadlSST1 global SST compilation (1 degree square resolution) for the period 1900 – 2006 (14, 15) (Fig. 1A and C). The composite data set contains 16,472 annual records, with corals ranging 10 – 436 years in age, most of which were collected in two periods covering 1983 – 1992 and 2002 – 2005 (Fig. 1B).

Preliminary exploratory analysis of the data showed strong declines in calcification for the period 1990 – 2005 based on growth records of 189 colonies from 13 reefs. Despite high variation of calcification between both reefs and colonies, the linear component of the decline was consistent across both reefs and colonies for 1990 – 2005. Of the 13 reefs, 12 (92.3%) showed negative linear trends in calcification rate with an average decline of 1.44% yr-1 (SE=0.31%), and for the 189 colonies 137 (72.5%) showed negative linear trends with an average decline of 1.70% yr-1 (SE=0.28%). To determine if this decline was an ontogenetic artifact, we compared these findings with similar analyses of the last 15 years of calcification for each of the remaining 139 colonies sampled prior to 1990. For this group, linear increases and declines were approximately equal in number, with 29 of the 56 reefs (51.7%) declining at an average rate of 0.11% yr-1 (SE=0.18%), and 68 of the 139 colonies (48.9%) declining at 0.16% yr-1 (SE=0.21%). This strongly suggests the 1990–2005 decline in calcification was specific to that period, rather than reflecting ontogenetic properties of the outermost annual growth bands in coral skeletons.

Due to the imbalance of sampling intensity over years and the desire to focus on time scales varying from a few years to centuries, the records were broken into two data sets for further analyses. The 1900 – 2005 data set contained all 328 colonies, whereas the 1572 – 2001 data set focused only on long-term change, and contained 10 long cores from colonies that covered all or most of that period.

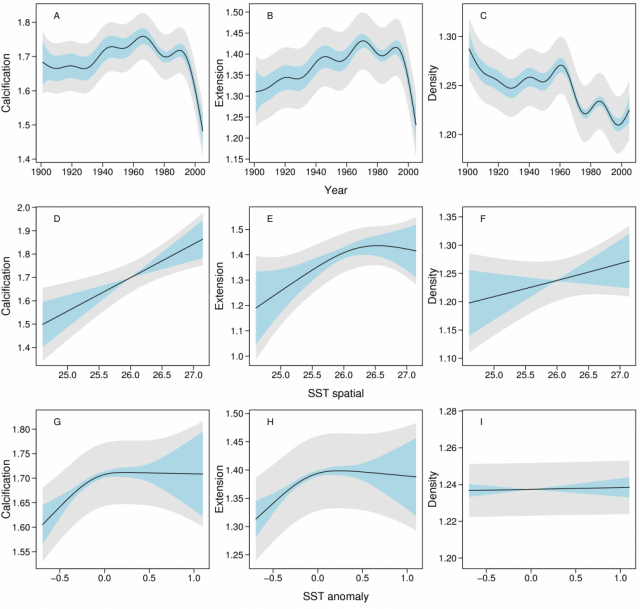

The dependencies of calcification, extension and density of annual growth bands on year (the year the band was laid down), location (relative distance of the reef across the shelf and along the GBR) and SST were assessed using linear mixed effects models (16; SOM). SST co-varies strongly with space and year (Figs. 1A, 1C), and to understand this confounding and assist in the interpretation of temperature effects, SST was partitioned into three components; the large-scale spatial trend (SST-SPAT; predominantly latitudinal), the long-term temporal trend (SST-TEMP) and the anomalies (SST-ANOM). The latter represent annual deviations from the large-scale and long-term trends in SST. The models included fixed effects in year, SST components, location, and random effects in reef, colony and year (SOM). Fixed effects were represented as smooth splines, with the degree of smoothness being determined by cross-validation (17). Results are illustrated through partial effects plots. Three sets of analyses were conducted; the first and second focused solely on temporal change and used the 1900 – 2005 and 1572 – 2001 data sets, whereas the third used only the 1900 – 2005 data set but also included the three SST components and relative distance across the shelf and along the GBR.

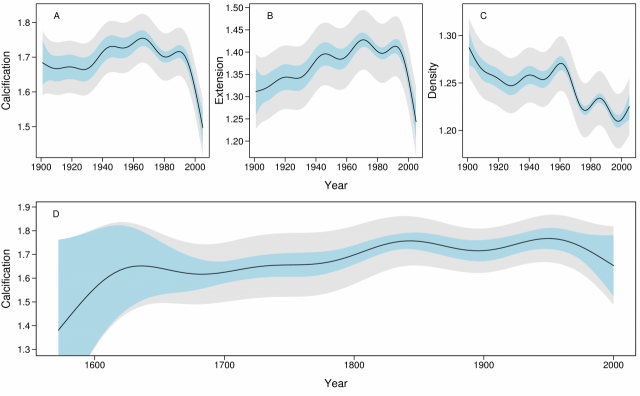

The temporal models of calcification, extension and density from the 1900 – 2005 data showed strong patterns of change (Fig. 2A - C). The rate of calcification increased from ~1.67 g cm-2 yr-1 in the period 1900 – 1930 to a maximum ~1.76 in 1970, but since 1990 has declined from 1.76 to 1.51 g cm-2 yr-1, an overall decline of 14.2% (SE=2.3%). The rate of this decline has increased from 0.3% yr-1 in 1990 to 1.5% yr-1 in 2005. The decline in calcification was largely due to the decline in extension from 1.43 to 1.24 cm yr-1 (13.3%, SE=2.1%). Density varied non-linearly from 1.24 to 1.22 g cm-3 (1.7%; SE=1.9%) over the period 1990–2005.

The 1572 – 2001 data showed calcification increased in the 10 colonies from ~1.62 g cm-2 yr-1 prior to 1700 to ~1.76 in ~1850, after which it remained relatively constant prior to a decline from ~1960 (Fig. 2D). However, this finding should be treated with caution due to the small sample size (7 reefs and 10 colonies).

Smooth terms in the three SST components and two spatial predictors (across and along the reef) were then added to the temporal models of the 1900 – 2005 data. SST-TEMP and across and along the GBR were non-significant and were omitted from all models (SOM), and year, SST-SPAT and SST-ANOM were retained (Fig. 3). The models showed that calcification varied little between 1900 – 1990, followed by a decline since 1990 from 1.76 to 1.49 g cm-2 yr-1, or 15.4% (SE=2.3%). As with the purely temporal model, this was largely due to a decline in extension rate from 1.43 to 1.24 (13.3%, SE=2.1%). The variation in density over this period was indistinguishable from the purely temporal model. Calcification also increased linearly with SST-SPAT at a rate of 0.122 g cm-2 yr-1 oC-1 (SE=0.041), corresponding to an increase of 0.36 g cm-2 yr-1 from south to north of the GBR due to the 3ºC mean temperature difference. Calcification also decreased with negative SST-ANOM values, but was highly variable for positive SST-ANOM.

The causes for the GBR-wide decline in coral calcification of massive Porites remain unknown, but this study shows that causes are likely large-scale in extent, and that the observed changes are unprecedented within the last 400 years. Cooper et al. (2008) previously demonstrated a 21% decline (1988 – 2002) in the calcification rate of 38 small Porites colonies, however the study was limited to two GBR inshore locations, comprised short time series thereby precluding comparison with earlier periods, and local environmental effects such as coastal influences could not be excluded. Factors known to determine coral growth and calcification include space competition, water quality, salinity, diseases, irradiance, currents, large-scale and long-term oceanographic oscillations, SST, temperature stress, and carbonate saturation state (6, 10, 18). Competition with neighboring corals is unlikely to have intensified during a period when coral cover has either remained similar or declined on most GBR reefs (7). Terrestrial runoff and salinity, whilst potentially affecting inshore reefs (19), are also unlikely causes since calcification declines at similar rates on offshore reefs away from flood plumes. Diseases can also be excluded since only visibly healthy colonies were sampled. Benthic irradiance depends on turbidity and cloud cover, but there are no data suggesting they have recently changed at GBR-wide scales. The Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation has been associated with changing currents and pH in a lagoon (20), however these and other large-scale long-term oceanographic oscillations can be excluded as they would have affected Porites calcification not only post-1990 but throughout the observation period.

Hence, by excluding these potential alternatives, we suggest that SST and carbonate saturation state are the two most likely factors to have affected Porites calcification at a GBR-wide scale. SST is an important environmental driver of coral growth. Our data confirmed previous studies (10, 21) that coral calcification increases linearly with large-scale mean annual SST. However, studies addressing shorter time periods show declining calcification at both high and low SST (22, 23, 24), and that thermally stressed corals have reduced calcification for up to 2 years (18). In our study, calcification was likewise reduced during cooler than average years (negative SST-ANOM). However, during warmer years it was highly variable, suggesting increasing calcification in some warm years but declines in others. This is possibly due to the year-averaged SST-ANOM inconsistently reflecting short hot periods that reduce calcification during warm years. The recent increase in heat stress episodes (25) is likely to have contributed to declining coral calcification in the period 1990 – 2005. The supersaturation of tropical sea surface waters with the calcium carbonate mineral forms, calcite and aragonite, is considered a prerequisite for biotic calcification, with saturation state being a function of pH and temperature. Since industrialization, global average atmospheric CO2 has increased by ~36% (from 280 to 387 ppt), the concentration of hydrogen ions in ocean surface waters has increased by ~30% (0.1 pH change), and the aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) has decreased by ~16% (6, 26). Studies based on meso- or microcosm experiments show that reduced Ωarag, due to the doubling of CO2 compared with pre-industrial levels, reduces the growth of reef-building corals by 9 – 56% (6), with most of these experiments suggesting a linear relationship between calcification and Ωarag. Ωarag data from the GBR or adjacent waters are sparse, but estimates of a global decline in Ωarag of 16% since the beginning of global industrialization are similar in magnitude to our finding of a 14.2% decline in calcification in massive Porites. However, the decline in calcification observed in this study began later than expected based on the model of proportional absorption of atmospheric CO2 by the oceans surface waters (26). Thus our results may suggest that, after a period of a slight increase in extension and prolonged decline in density, a tipping point has been reached in the late 20th century. The non-linear and delayed responses may reflect synergistic effects of several forms of environmental stress, such as more frequent stress from higher temperatures and declining Ωarag. Laboratory experiments have provided the first evidence documenting strong synergistic effects on corals (27), but clearly more studies are needed to better understand this key issue. Laboratory experiments and models have predicted negative impacts of rising atmospheric CO2 for the future of calcifying organisms (5, 6). Our data show that growth and calcification of massive Porites in the GBR is already declining, and is doing so at a rate unprecedented in coral records reaching back 400 years. If Porites calcification is representative of other reef-building corals, then maintenance of the calcium carbonate structure that is the foundation of the GBR will be severely compromised. Verification of the causes of this decline should be made a high priority. Additionally, if temperature and carbonate saturation are responsible for the observed changes, then similar changes are likely to be detected in the growth records from other regions and from other calcifying organisms. These organisms are central to the formation and function of ecosystems and food webs, and precipitous changes in the biodiversity and productivity of the world’s oceans may be imminent (28).

References

1. J. Lough, Journal of Environmental Monitoring 20, 21 (2008).

2. K. Caldeira, M. Wickett, Nature 425, 365 (2003).

3. J. A. Kleypas et al., Science 284, 118 (1999).

4. S. Ohde, M. M. Hossain, Geochemical Journal 38, 613 (2004).

5. O. Hoegh-Guldberg et al., Science 318, 1737 (Dec, 2007).

6. J. M. Guinotte, V. J. Fabry, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1134, 320 (2008).

7. J. Bruno, E. Selig, Public Library of Science ONE 2, e711. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000711 (2007).

8. K. E. Carpenter et al., Science 321, 560 (2008).

9. J. Lough, D. Barnes, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 211, 29 (1997).

10. J. M. Lough, D. J. Barnes, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 245, 225 (2000).

11. D. Knutson, R. Buddemeier, S. Smith, Science 177, 270 (1972).

12. M. Gagan et al., Quaternary Science Reviews 19, 45 (2000).

13. B. E. Chalker, D. J. Barnes, Coral Reefs 9, 11 (1990).

14. R. W. Reynolds, N. A. Rayner, T. M. Smith, D. C. Stokes, W. Wang, Journal of Climate 15, 1609 (2002).

15. N. A. Rayner et al., Journal of Geophysical Research 108, doi:10.1029/2002JD002670 (2003).

16. N. E. Breslow, D. G. Clayton, Journal of the American Statistical Association 88, 9 (1993).

17. G. Wahba, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B 45, 133 (1983).

18. A. Suzuki et al., Coral Reefs 22, 357 (2003).

19. M. McCulloch et al., Nature 421, 727 (2003).

20. C. Pelejero et al., Science 309, 2204 (2005).

21. F. Bessat, D. Buigues, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 175, 1 (2001).

22. A. Marshall, P. Clode, Coral Reefs, 218 (2004).

23. C. D. Clausen, A. A. Roth, Marine Biology 33, 93 (1975).

24. T. Cooper, G. De'ath, K. E. Fabricius, J. M. Lough, Global Change Biology 14, 529 (2008).

25. J. M. Lough, Geophysical Research Letters 35, L14708 (2008).

26. J. C. Orr et al., Nature 437, 681 (2005).

27. S. Reynaud et al., Global Change Biology 9, 1660 (2003).

28. J. E. N. Veron, A reef in time: the Great Barrier Reef from beginning to end (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2008), pp. 280.

29. Acknowledgements: We thank Monty Devereux, Eric Matson, Damian Thomson and Timothy Cooper for slicing and x-raying the corals. This study was funded by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).